Should Differences in Biblical Manuscripts Scare Christians?

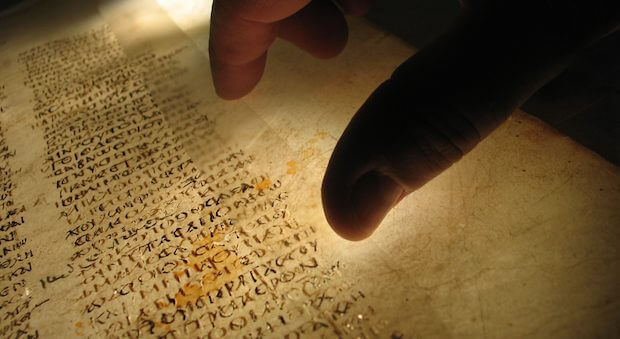

Image: codex-sinaiticus.net

Many Christians are troubled by differences in wording among various Greek New Testament texts: The Bible has scribal errors in it? Then how can I be sure what I’m reading is God’s word?

I have taught New Testament Introduction to beginning seminary students for many years, and I’ve come to realize that there’s a simple path to clarity and comfort regarding this issue—simpler than diving into excessively complicated details about ancient manuscripts written in languages few Christians have the training or experience to assess reliably.Here are three reasons Christians should not be troubled by textual variants.

1. No theologies or denominations claim a particular text

Yes, there are differences between Bible manuscripts, and from a certain perspective, they can look alarmingly serious. For example, those manuscripts (and resultant Bible translations) which “omit” 1 John 5:7 seem to some readers to undermine the doctrine of the Trinity.But there’s a simple way to demonstrate how trivial the differences between ancient manuscripts really are in terms of their effect on the body of truth that the Bible reveals. We have lots of doctrinal differences within Christianity, right? But there are no Calvinist manuscripts/versions, Arminian manuscripts/versions, Pentecostal, Reformed, Presbyterian, Episcopal, Congregationalist, Egalitarian, Complementarian, Integrationist, Cessationist, or Continuationist manuscripts/versions.

Take any systematic theology textbook you want, and the set of proof texts offered for particular points is for all practical purposes version-independent—the authors don’t care which translation you use, so they just give references. The difference in doctrinal character among the various manuscripts and translations is very close to zero. The “omission” of 1 John 5:7 (in the judgment of almost all textual scholars, those words were actually added very late in the manuscript tradition, not appearing in Erasmus’ Greek New Testament until its third edition) has not caused a single Christian denomination to descend into Unitarianism—because the New Testament elsewhere still clearly teaches the doctrine of the Trinity. In fact, none of the Greek writings of the early church ever mentions this passage—even in their discussions of the Trinity! If the church fathers recognized and formulated that vital doctrine without referring to this verse, then its presence in the New Testament of their day is highly unlikely, and certainly its absence from a Bible text or translation today constitutes no defect in doctrinal character.

If the differences between Greek texts were doctrinally significant, you would expect theologies and tribal groups to grow out of distinctive readings of those texts—you would expect certain sects to adopt Greek texts as theological banners. But compare the positions of Majority text advocates, Textus Receptus devotees, and eclectic text users on the core doctrines of the historic creeds and you’d be hard pressed to find a doctrinal difference for which they claim support in their favored New Testament text as opposed to others.

Different Christian tribes bring somewhat different lenses to the Bible, but it’s the lenses that differ, not the Bible.

2. Even if we had absolutely perfect copies, the work of interpretation would still have to go on

If we had the originals themselves—the very pieces of papyrus Paul used to compose Romans and Ephesians, for example—or if no copies contained any textual variants at all, unlocking the Bible’s power would still require us to do exactly what we do now: search for Scripture’s wisdom as for hidden treasure, interpreting carefully, comparing Scripture with Scripture, and making relevant personal application. Nothing would change except that we would be able to dismiss from our minds the possibility that the text we’re working with may not preserve God’s exact inspired words with complete perfection. But my own weaknesses as a reader expose me to far more significant misunderstanding than the manuscript differences do, so by far the greatest problems that God must overcome in order to talk to me are within me, not within the transmission process.3. Pristine perfection is a property of the next world, not (generally) of this one

It’s true that the Greek and Hebrew manuscripts we have can’t all preserve the exact wording of the originals (and by definition, a translation cannot do so). The fact that no two manuscripts are identical down to the jots and tittles means that at most only one manuscript of any given Bible book can be “perfect.” All manuscripts of any size (some are less than a page) contain some obvious scribal slips, so it seems clear that God hasn’t given us access to the one “perfect” manuscript of any book of the Bible.The very strong pattern God has ordained is that pristine perfection is a property of the next world, not this one, so I just need to conform my expectations to that reality. The textual imperfections that generate so much angst and controversy are well within an easily tolerable range, and, while of course we must make the wisest choices we can, we can be completely at ease that, with the exception of extreme paraphrases or Bibles translated by cult groups, any Bible we may use is fully trustworthy as God’s Word. We need not fear that some of these Bibles are the devil’s. Where does Scripture warn us to ferret out and avoid the devil’s Bibles? It seems that, in his sovereignty, God has arranged that the very few Bibles possibly worthy of that categorization are obviously so, not subtly so.

Conclusion

If the manuscripts were hopelessly confused across their whole bodies of text about whether Paul’s gospel was justification by faith plus works of the law or justification by faith without works of the law; or if some manuscripts said that the baptism of the Spirit includes speaking with tongues and some said the opposite; or if some promised that Jesus would rapture his church before the Tribulation while others took what we now call a postmillennial view—then identifying the correct text would obviously be a matter of theological importance. Jesus called some matters of the law “weightier” than others (Matt 23:23)—if serious differences existed among those, we’d have a serious difficulty.But the variations we have among manuscripts raise far different questions: does the inspired text say we have redemption through Christ’s blood twice or only once? Does it testify to Jesus’ atoning blood 44 times or only 43? Does John say “his anointing” or “the same anointing” (one letter different in Greek) in 1 John 2:27?

Even the two major passages that are textually questionable—Mark 16:9-20 and John 7:53–8:11—do not affect the doctrinal character of the New Testament. The former largely duplicates material found in the other gospels; the latter illustrates truths we know well from other passages: the scribes and Pharisees are self-righteous and Jesus is forgiving and yet demanding. If such textual variants represent Satan’s best attempt to corrupt the doctrinal character of Scripture, then God is clearly keeping him on a very short leash, indeed. Oh, for a life full to the brim of such problems as these!

The bottom line is that God has arranged things so that I can take any good English Bible translation, based on any textual or translation philosophy, treat it as if its every English word were straight from him, and get everything I need from that Bible to know, love, and live for him in a way that will bring Christ’s “Well done!” when I stand before him. And what more is there to life? Wherever a problem in transmission or in my own reading may tend to lead me astray, there’s a corrective somewhere else in Scripture that, when I interpret the parts in light of the whole, will keep me within bounds.

Randy Leedy, PhD, has taught Greek and New Testament at Bob Jones Seminary since 1994. He is the author of Greek New Testament Sentence Diagrams and Love Not the World.

No comments:

Post a Comment